Composer Correspondence and the art of developing a new piece

1 October 2024

Striking Stories: a series of posts written by volunteers unearthing the fascinating stories within The Evelyn Glennie Collection.

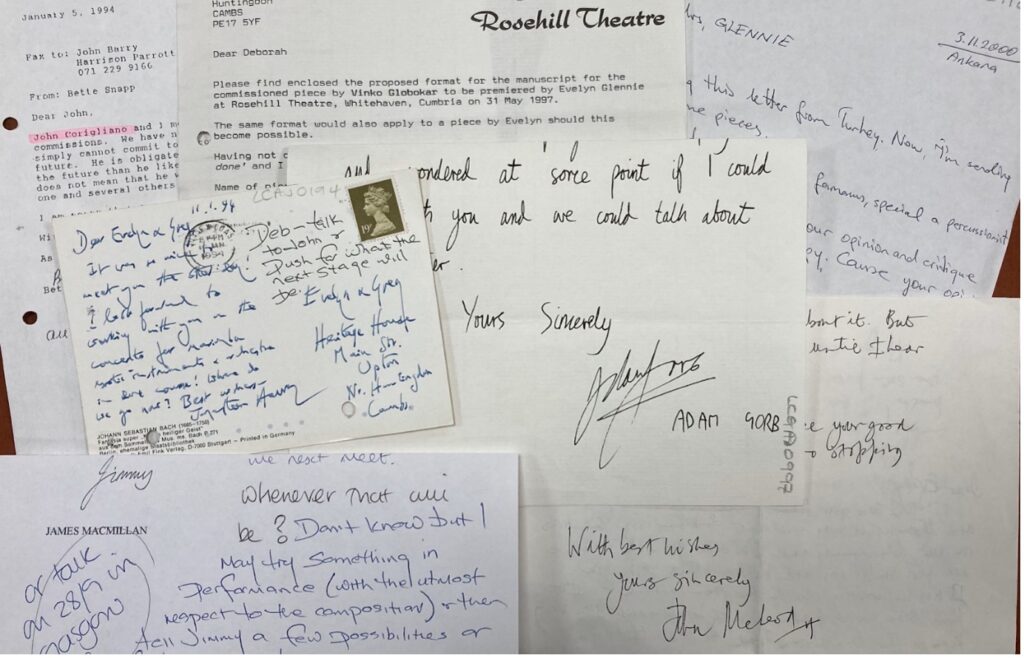

For the past few months I have been occupied in sorting the voluminous amount of correspondence that Evelyn has accumulated with a huge number of composers (some 480 and counting!) over the course of her professional career.

This has been a challenging but fascinating task, during which I have certainly learnt a lot about the process of composing and about the potential use of the wide variety of instruments that a percussionist can be called on to play in any one piece of music.

Once I had completed the physical process of sorting, reading and arranging the correspondence in a chronological order (and dealing with a lot of staples!) I could begin cataloguing it.

Quite the repertoire

The composers include many household names – Sir Harrison Birtwistle, Richard Rodney Bennett, Andrzej and Roxanna Panufnik, Sir James MacMillan, Steve Reich and Iannis Xenakis – as well as other less well-known names, and the quantity of correspondence for each person varies enormously too, from single letters to 50 or 60 items, and in the case of Nebojša Jovan Živković, 120!

The road to getting a piece written, published and performed is clearly not without its problems, not to mention the whole negotiating process of having first recording rights of the piece. Hence it can often be an extremely long drawn-out business.

An exciting aspect of this correspondence is that you can follow the whole process from the very first suggestion of a new work, which might come either from the composer or from Evelyn, right through to the performance at a world premiere. Evelyn is always keen to stretch herself artistically and is open for new works to be written that will challenge perceived norms, as she wrote to Mark Anthony Turnage when they were discussing the work that became the double concerto Fractured Lines:

‘The idea of both soloists hanging onto their identity is great but I also see a piece that breaks all boundaries, musically, virtuosically and even visually.’

Some comments are very down to earth, demonstrating the human qualities of those involved, as shown in the following:

The idea doesn’t always get off the ground, as was the case when an approach was made to Thomas Adès to which his publisher replied:

‘I’m delighted that Evelyn is interested in Tom – however the whole world has also recently discovered him.’

Not surprisingly after this polite brush off, nothing came of the suggestion.

A complex process of creation and negotiation

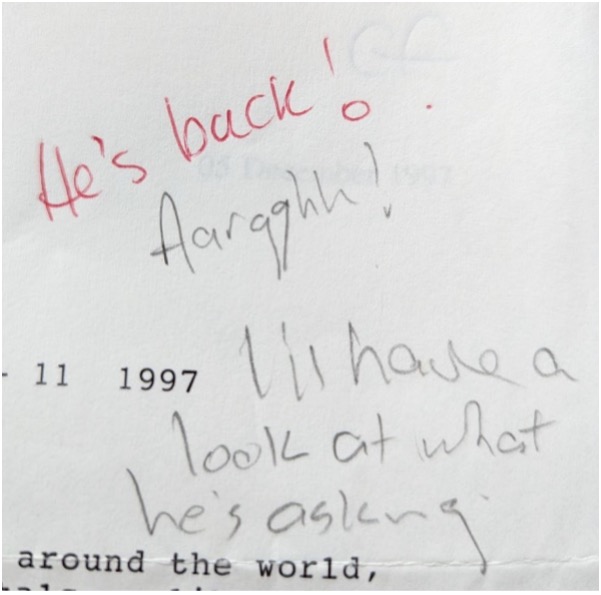

It can often take a few months before any meetings can be arranged between the composer and Evelyn in any country where their schedules might coincide, with commitments on both sides being planned sometimes years ahead. It appears that some composers were not always very easy to deal with. Here the letters from Evelyn’s office are very interesting, shedding light on the practicalities of such arrangements. They often have comments written by hand on them, both by Evelyn and her office and agents’ staff, which are quite illuminating at times! As an example, Evelyn herself wrote about one piece:

“I cannot see myself playing it as it is not quite meaty enough either musically or emotionally although it is still very attractive…. Write the letter nicely and encouragingly!”.

Very often Evelyn will suggest that the composer should come to her office to view her ever-increasing collection of percussion instruments to get some idea of the range of what is available, although this wasn’t always possible since the composer could easily be living on the other side of the world. The American composer John Corigliano flew to the UK from New York specifically to spend a day with Evelyn exploring the effects of playing with different mallets.

Once there is some agreement on both sides simply about the idea of a new piece being written, one of the first hurdles to be overcome is the thorny question of funding, with different composers commanding widely different rates of pay. In 2000 Evelyn’s agent warned her that one composer would charge US$75,000 for a concerto to be written by the end of 2001.

And because this correspondence includes many letters from Evelyn’s agents you can get a good impression of exactly how complicated this process often is. Many orchestras and music organisations may be approached, to act as a commissioning consortium, obviously in many countries around the world, before any firm commitments are made. Then there is the programming of a premiere, usually some years into the future and a long time before the piece is actually completed.

Long before this happens, there is often a great deal of correspondence between the composer and Evelyn about the details of the piece; sometimes the composer will need to confirm various musical aspects of their composition, such as exactly what range a particular instrument has, or how to indicate a specific effect that they want. Christopher Rouse wrote about his work Der Gerettete Alberich:

‘I hope Evelyn won’t take this amiss but as a reformed percussion player myself I tend to be pretty certain of the stick indications I’ve made. Certainly though, I don’t want to be uncooperative and I’m sure that many of Evelyn’s choices will be more than appropriate.’

Then there is the practical aspect of planning the layout of a sizeable number of instruments on a stage, which for a piece called My Dream Kitchen by Django Bates amounted to some 60 different items including utensils and pieces of food! As Evelyn wrote to Jody Talbot about his work Incandescence

‘Above all I’d like to try & ensure that the set-up remains quite compact and that the audience have the impression of a single instrument (albeit made up of many individual units) being properly explored & exploited as befits a concerto.’

Also, there is the question of whether it is physically possible for the player to switch between the different instruments at speed, particularly if different sticks or mallets are needed, which is generally the case. As Evelyn wrote to Stewart Wallace about his work The Cheese and the Worms:

‘In Bar 28 do you mean to actually play cymbals with bare hands? There is no time to pick up stix so bare hands it is! It’s not possible to do any rimshots on timbales due to the fact that I’m using vibraphone stix every time the timbales are played.’

After the first performance, or indeed subsequent performances, there are usually some complimentary letters from the composer, or in the case of Andrzej Panufnik, his widow, who wrote

‘Your performances of Andrzej’s Concertino are particularly special to me, not only because you play the work with such brilliance and poetry, but also because Andrzej thought the world of you as a musician and colleague’.

Sometimes there may be suggestions from either side as to any changes or improvements that might be made after the premiere, such as John Corigliano wanting to change the title of his Concerto from Triple Play to Conjuror because of the dramatic physicality of her performance.

Evelyn wrote after the premiere of Barbara Thompson’s Greek Dances:

‘Things need to be more slick between movements. It would be nice to recite the words before each movement and this would eliminate awkward silences’.

Occasionally things do not go well, as Evelyn wrote after one performance:

‘The performance we gave of your piece was, frankly, unacceptable….I don’t think I have ever had the experience of giving such a bad performance before.’

Owing to the sheer length of Evelyn’s career the physical nature of the correspondence changes over time, starting with handwritten or typed letters, then there are faxes (which haven’t always lasted very well, some are extremely faded and almost impossible to read), and then emails. As Evelyn recently pointed out to me:

….“in fact meetings with composers can happen wherever they are based in the world due to the accessibility of online platforms such as Zoom, Teams, Google Meet etc. No longer do we have to be in the same continent, country or time zone but instead the switch of a computer allows us to suddenly be conjuring a new piece with a composer from any part of the world. It also means less written correspondence.”

I have to say that I find the letters, particularly the handwritten ones, the most interesting to read, because you can really get an idea of the character and personality of the people involved, which doesn’t come across nearly so well in an email.

This archive of 3058 papers is an internationally important primary resource, for amateurs and professionals alike, shedding much light as it does on the whole process of composing, publishing and performing and I really hope that other people will find this aspect of The Evelyn Glennie Collection as interesting and informative as I have and that it will continue to be used for academic research well into the future.

written by Penelope Tolmie, October 2024